Menu

WildFlowers on the trail

Previous slide

Next slide

And why take ye thought for raiment? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin:

And yet I say unto you, That even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.

Wherefore, if God so clothe the grass of the field, which to day is, and to morrow is cast into the oven, shall he not much more clothe you, O ye of little faith?

Therefore take no thought, saying, What shall we eat? or, What shall we drink? or, Wherewithal shall we be clothed?

(For after all these things do the Gentiles seek:) for your heavenly Father knoweth that ye have need of all these things.

But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you.

Matthew 6:28-33

Click on the links below for information regarding nature tours to the waterfalls and wildflowers of Upstate South Carolina. Several tours with State naturalists are conducted in Spring to view the wildflowers at several State Parks.

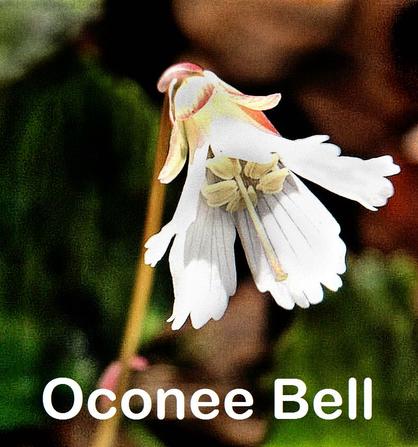

OCONEE BELL HISTORY

Oconee bells, thought lost to science for almost a century, grow in the moist soil of Oconee County in Upstate South Carolina.

Shortia galacifolia is a wildflower nearly driven to extinction by both glacial activities and its restrictive germination requirements, which limit its natural range to a few watersheds in the Appalachian Mountains along the North and South Carolina border.

The story associated with the naming of Oconee bells and the search for this plant is perhaps the best story of 19th-century American botany.

Oconee bells were discovered in 1788 by French botanist André Michaux while he explored the mountains of the Carolinas. He recognized from the seed capsules that it was a new species and possibly a new genus.

Michaux collected a specimen to take back to his herbarium in Paris. The specimen was pressed and dried, but laid ignored for 50 years until a visit by American botanist Asa Gray. Although the material consisted of only a few leaves and a single seed pod, Gray realized this plant was new to science. Upon returning home he organized an expedition to the “high mountains of Carolina” where Michaux had discovered the mysterious plant.

After searching for two years, Gray failed to find the plant. So he described and named Michaux’s herbarium specimen Shortia galacifolia after Dr. Charles W. Short, botanist and physician of Louisville, Kentucky. The specific epithet galacifolia refers to the leaves resembling those of Galax.

Ironically, Charles Short never saw the plant because he died 14 years before it was rediscovered. The plant’s common name, Oconee, is the name of the Indian tribe once endemic to the area.

The rediscovery of Shortia became an obsession for many botanists. The quest to find it had been called the “Holy Grail of 19th-century botany.” All searches were unsuccessful and the plant’s whereabouts remained shrouded in mystery for nearly the next half century. Eventually it was discovered not by a famous plantsman but by a teenager named George Hyams.

In May of 1877, Hyams found a patch of shortia growing along the Catawba River in North Carolina some 70 miles in a direct line from the site of Michaux’s discovery. He brought samples of it back to his father, M.E. Hyams, an herbalist, who did not know the plant. Eighteen months later, he brought it to a friend, Joseph W. Congdon in Rhode Island.

Congdon wrote to Gray, telling him that shortia had been rediscovered. After giving up all hope of ever seeing a living shortia Gray was ecstatic. The search of nearly 40 years was at an end.

Two years later, Gray organized an excursion to see the plant growing in the wild. Hyams led a party composed of Gray’s family and botanical friends, including Dr. Charles S. Sargent of Massachusetts.

A little colony of shortia grew in a location well-protected by rhododendrons and magnolia. They were few but vigorous and healthy, growing alongside Mitchella repens, Asarum virginicum, and Galax aphylla. Gray finally saw shortia in its native habitat, but he never visited the locale where Michaux had found the original plant.

It is said that Sargent, who was not satisfied with the results of the excursion, found shortia in the autumn of 1886 while hunting for Magnolia cordata.

Unfortunately, Sargent later forgot where he found the leaf he had identified. The Boynton brothers, who were part of the search, eventually found it growing beside a stream and gathered small amounts to bring back. Sargent placed one of these plants in Gray’s hands. The plants came from the headwaters of the Keowee River in South Carolina, the original location that Michaux found shortia 100 years earlier.

Many honors were bestowed onto Dr. Gray, including being elected to the Academie des Sciences of the Institute de France, one of the most coveted rewards to a scientific man. Yet the discovery of shortia gave him a greater satisfaction.

In the 1970s, the Jocassee area was flooded by the Duke Power Co. The original collection location is now submerged below the waters of Lakes Jocassee and Keowee.

Less than 50% of shortia’s habitat survives, mostly on stream banks feeding the lake, and are in danger of erosion from wave action. Fortunately, the survival of shortia has been enhanced by its cultivation in countless gardens, such as the Leonard J. Buck Garden.

From April to early May, this beautiful discovery of Michaux shows off on the north-facing slopes of the rock outcropping Polypody. The solitary white to pinkish flower has five fringed petals atop a six-inch salmon-colored, leafless stalk. The flowers peek out over the previous season’s foliage two weeks before the new leaves appear.

In well-established sites this plant can form a dense groundcover covering a huge area. It is surprisingly hardy for such a rare plant. Once a population is established, it spreads vegetatively with rhizomes, eventually forming low, ruffled mounds. The evergreen leaves are rounded and shiny with scalloped edges. In the fall and winter, the leaves turn a reddish-bronze color.

S. galacifolia is long-lived and improves each year. It grows best in moist, peaty soil in light shade. Mulching around the plant with crushed oak leaves and or pine needles in spring helps root growth. The roots are very thin and prone to damage by drought and over-fertilization. Eventually, deeper roots will grow from the center of the plant, but it is essential to site the plant in a place that will not dry out.

The story of this legendary plant abounds with ironies. Shortia was discovered by a man who didn’t name it, named for a man who didn’t see it, by someone who didn’t know where to locate it.

Now you know where one of the most interesting plants in North America lives!

A very good place to find Oconee Bells is Devil’s Fork State Park in Upstate South Carolina.